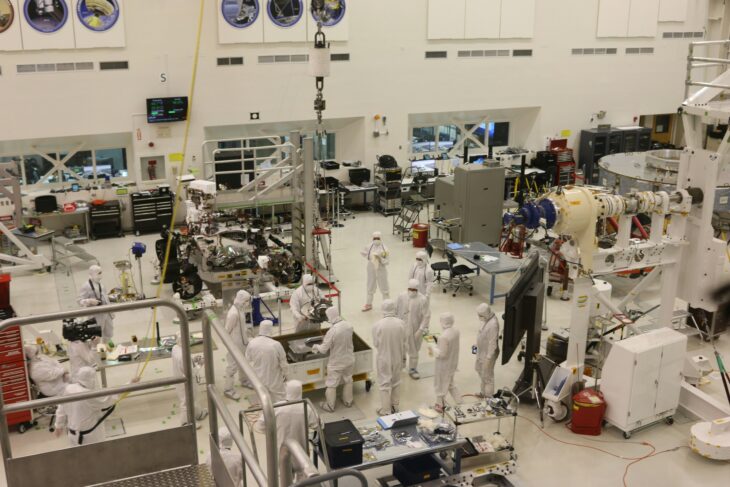

NASA follows strict rules to ensure that Earth microbes do not accidentally contaminate other worlds, and vice versa. These rules, referred to as planetary protection protocols, originate from the Outer Space Treaty signed in 1967 by the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom, and the United States. If a spacecraft carries bacteria or other Earth-based life forms to Mars, Europa, or Enceladus, it could confuse future life-detection missions or even harm potential alien ecosystems. For this reason, spacecraft are built in highly controlled environments called cleanrooms, designed to be as sterile as possible. Cleanrooms follow strict protocols, including filtered air, controlled temperatures, and even ultraviolet radiation to reduce microbial contamination.

Yet, even in these ultra-clean environments, a few stubborn microbes manage to persist. Researchers from the University of Houston recently studied one such microbe: Tersicoccus phoenicis, a bacterium previously discovered in a spacecraft assembly cleanroom. The scientists wanted to determine how these microorganisms persist in such supposedly “sterile” environments and what this means for space exploration.

The research team discovered that T. phoenicis can enter a dormant, inactive state that allows it to survive extreme stress such as nutrient or water scarcity. Because dormant cells stop dividing, they remain alive but undetectable by standard methods that rely on visible colony formation. Many bacteria survive such conditions by forming protective spores, but T. phoenicis lacks the genes required for sporulation, indicating that it relies on a different survival strategy.

To confirm that the microbes were dormant, the researchers grew T. phoenicis under a nutrient-limited environment designed to mimic a cleanroom. They tracked the bacteria’s growth by measuring their optical density in liquid cultures and counting how many colonies they formed on solid agar. They found that T. phoenicis initially grew well but then stopped forming colonies after a few days.

Next, the team analyzed T. phoenicis’s genome. They found that it has genes associated with a kind of reversible dormant state found in other non-spore-forming bacteria, referred to as viable but not culturable or VBNC. Bacteria in this state remain alive but do not form structurally distinct spores, making them visually indistinguishable from dead cells under a microscope. VBNC bacteria are more challenging to detect than spore-forming bacteria, which scientists can identify with specific staining techniques.

To confirm that the bacteria were dormant and not dead, the researchers used a protein called a resuscitation-promoting factor or Rpf. This protein breaks down the VBNC bacteria’s cell walls and releases signalling molecules that trigger metabolic activity and cell division, helping them “wake up” and start growing again. They inserted the gene that forms Rpf into the common bacterium E.coli, causing it to produce the protein. They extracted the protein from E. coli and transferred it to the dormant T. phoenicis cells. The bacteria started growing again, suggesting that they were indeed alive but in a VBNC state.

Next, the team tested how well T. phoenicis could survive drying out, a common stress in cleanrooms. They air-dried the bacteria on sterile agar plates for 48 hours and for 7 days, then tried to grow them again. After 48 hours, only about 0.1% of the bacteria were able to grow, and after 7 days, they were completely unable to grow. This result showed that T. phoenicis quickly enters dormancy when faced with dessication. However, when the researchers added Rpf-containing media to the bacteria, they recovered and grew even after 7 days of drying.

While scientists in the past had observed VBNC in some disease-causing bacteria, these researchers were the first to demonstrate it in cleanroom bacteria like T. phoenicis. They suggested this adaptation could mean that VBNC dormancy is a common survival strategy for microbes in cleanrooms. Cleanrooms are hot, dry, and nutrient-poor, similar to some extraterrestrial surfaces. So, if VBNC bacteria like T. phoenicis escape detection during cleaning, they could survive a space mission and interfere with life-detection.

The team concluded that understanding how T. phoenicis survives in such environments can help scientists better predict which microbes might persist beyond Earth and improve planetary protection protocols as exploration expands. They suggested that this discovery could also help doctors develop better sterilization procedures and strategies against hard-to-kill, antibiotic-resistant pathogens.