DNA is the molecule that carries our genetic information. It also comes with a partner molecule, RNA, that codes for and creates the building blocks of life, amino acids. DNA, RNA, and amino acids come together to form larger molecules we call genes. Genes code for proteins that either serve a specific function or make up other large biological molecules.

Sometimes, the RNA within genes has faults. These faults can be as extreme as causing a protein to become deadly. Incorrectly synthesized proteins that cause fatal diseases are called prions. Scientists think prion diseases may now be treatable, thanks to technology that can edit RNA, known as CRISPR.

Scientists have known that this treatment is theoretically possible since they first discovered bacteria using their own form of natural gene editing to fight off viruses. So, medical scientists from Harvard, MIT, and Case Western recently conducted a trial study of CRISPR’s ability to fight prion diseases. The team first had to determine where in the genome the corresponding RNA was faulty, and alter the corresponding genes responsible for prion disease. To find this faulty RNA, they had to identify its starting and ending points, called start/stop codons.

In the lab, the scientists took RNA from mice infected with a human prion disease. Then they used CRISPR to alter the faulty RNA on a molecular level, inserting new start/stop codons that would cut it off before it replicated, which they referred to as sgRNA. For the experiment, the scientists chose 3 versions of this modified RNA based on their efficiency in producing non-functioning proteins. The sgRNAs they chose were titled sgRNA, F-sgRNA, and F+E-sgRNA.

Next, they took a medically administerable virus, known as an adeno-associated virus, loaded it with the altered sgRNA, and injected it into mice infected with the same prion disease. They explained that if the method succeeded, it should stop the prions from replicating, preventing the associated disease.

To test this, the scientists used 2 small groups of mice injected with prion disease: the experimental group, which received the 3 optimized sgRNA types, and a control group that received no sgRNA. When both groups of mice were around 6 to 9 weeks old, the scientists injected them with different laboratory strains of a human prion disease, called a human prion isolate. When they were 7 to 10 weeks old, the scientists injected only the experimental group with the sgRNAs.

The scientists monitored the mice for 92 to 95 weeks and observed any changes in their behavior, weight, and lifespan. Then they compared the outcomes of the 2 groups to determine whether the main group’s health improved as a result of the treatment. The team found that the treatment extended the lifespans of the treated mice by nearly 60% on average compared to the control mice.

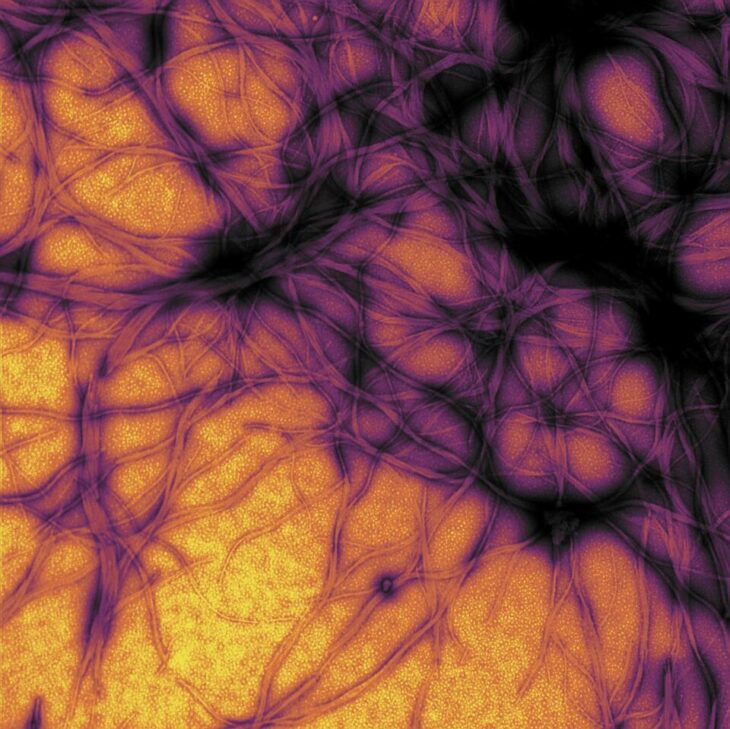

To measure the success of the experiment, the team also euthanized the mice at the end of the experiment and compared their brains. They were mainly concerned that the edited RNA would target the wrong gene, an error known as off-target editing. To check for off-target editing, they scanned the mice’s brains for potential side effects or other anomalies unrelated to prion activity. Their results indicated that substantial off-target editing had occurred.

They also checked for prion activity or inactivity to see the effects of their CRISPR technique on the intended RNA strands, known as on-target editing. To do so, they checked how much prion protein was in the mice by looking for antibodies created by the mice’s immune systems to target the specific prion. They found that the treated mice had around 4% to 40% lower levels of prion proteins than the control group. In the most successful case, the mice treated with the F+E-sgRNA had 43% lower prion protein levels.

The team concluded that CRISPR editing could help fight prion diseases in mice. However, the substantial amount of off-target editing that occurred would be detrimental to humans due to its unpredictable side effects. They indicated that future experiments will likely have to continue using mice or other lab animals, at least until researchers develop a technique refined enough to edit only the targeted genes. Nonetheless, they suggested that their results offer a positive step towards treating prion diseases in humans.